Frances Cleveland was an "influencer." At 21, she took the country by storm when news broke that she was to marry President Grover Cleveland, aged 49, in the White House.

Early in the morning of June 2, 1886, the presidential carriage waited for Frances Clara Folsom, her mother Emma and cousin Benjamin Folsom, to arrive by train. They had been staying in New York City since Decoration Day, which is now called Memorial Day. Rose Cleveland, sister of President Grover Cleveland, greeted Frances and her family. The newspapermen on that train swarmed them like modern-day paparazzi. Everyone wanted a glimpse of who was going to marry the President. Hawkins, the coachman, cracked his whip and the horses galloped to the White House, doing their best to avoid the sketch artists and reporters.

Frances Cleveland, once described by Mark Twain as “the young, the beautiful, the good-hearted, the sympathetic, the fascinating,” was about to charm Americans and anyone who had the good fortune to meet her. One year after her college graduation, she was about to become the youngest first lady. To prepare her for the role, she and her mother were sent abroad by the White House to visit seven European countries. They travelled for nine months so that Frances could learn about social customs, visit historic sites and prepare her trousseau in France– the items a bride needs such as garments and linens.

While waiting for his bride to arrive on their wedding day, President Cleveland was working and only took about two or three breaks to chat with Frances and her mother. He even went for a drive in the afternoon.

About 15 seconds before 7:00 p.m. in the vestibule, John Phillip Sousa raised his baton and the Marine Band played Mendelsohn’s “Wedding March.” The couple walked slowly down the stairs, and she was on his arm. President Cleveland was dressed in a black suit, and Frances looked stunning in a cream satin wedding gown.

Her corded satin dress was stiff enough to stand alone. Two scarves of India silk muslin crossed from her shoulders to her waist, Grecian-style. Below the waist on the left side, a piece of this silk flowed and nearly met her 15-foot-train that filled the length of the Blue Room. Orange blossoms, bows and small leaves trimmed the drapery around her neckline, down her bodice and around the bottom of her elbow sleeves. Frances was tall, about 5’7”. Her silk tulle veil, measuring almost six yards long, showcased her loosely pulled back dark brown hair and violet blue eyes. She wore no jewelry, held no bouquet, and carried a white fan.

A guest later described her as a “radiant vision of young springtime.” She loved flowers, and they surrounded her from the greenhouse. The Blue Room was filled with red, pink and white azaleas and camellias. Potted red begonias in the fireplace gave the illusion of warmth. Purple pansies, trimmed in yellow, sat on the east mantel tinged with ferns, and white pansies in this arrangement spelled out: “June 2d 1886.”

Approximately 30 wedding guests, including a few family members and Cabinet officers were present. Under the magnificent chandelier, The Reverend Dr. Byron Sunderland of the First Presbyterian Church performed the ceremony which lasted about ten minutes. When Frances said her vows, she switched the word from “obey” to “keep.” Reporters were not present at the ceremony but were allowed a last-minute look at the floral displays. Oh, one tried to bribe Phillip Sousa, but Sousa would not oblige.

Frances’ mother congratulated the couple first, followed by The Reverend Sunderland. The group moved to the East Parlor, decorated with rare palms and foliage and then the dining room for dinner. Potted plants, arranged pyramid style in the corners of the room, along with roses on the mirrors, continued the vision of springtime. The centerpiece was flowers in the shape of a ship about to set sail. On its masthead, the monogram, “CF.”

Grover gave Frances a diamond necklace. The couple gave their guests each a box with the wedding date on the cover, and inside was a piece of cake and a handwritten note. A 21-gun salute celebrated the wedding, and all church bells rang throughout the land.

At 8:30 p.m., President and Mrs. Cleveland left through a private exit in the Blue Room to the South Grounds and travelled by carriage to the railway. They boarded a special train to Deer Park, Maryland, 200 miles away, for a short honeymoon in a cottage on the crest of the Alleghany Mountains.

The reporters followed. This gave rise to the term “keyhole journalism” because they would do anything to sneak a peek. The newspaper men and the sketch artists waited in the treetops and around the properties to capture an image of the couple, especially the woman who charmed and fascinated the hearts and minds of Americans.

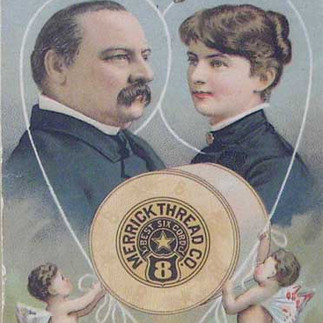

From that point on, Frances was not left alone. Enchanting, fashionable and kind, she had a lovely voice and a smile that never appeared the same way twice. Men adored her, and women wanted to be like her. Even President Cleveland became a better dresser and better with social graces. Her adoring public copied her hairstyles and fashion sense, and manufacturers wanted her to endorse their products.

From the Mark D. Evans collection, Avon, NY

Piano makers called to send pianos to the White House. She received sewing machines, fabrics, and perfumes. Her likeness was used as a product endorsement because she had the magic touch. The image of Frances Cleveland appeared on plates, jewelry, picture cards, textiles and glassware, and without her approval. Her image was used to sell so many things including needles and thread, headache remedies, and beauty products. For many magazines, she was their cover girl.

A real celebrity in the blooming age of newspapers and advertisements, First Lady Cleveland went “viral.” It was Frank-mania! If social media had existed back then, she would have been deemed an “influencer.”

In memory of Frances Cleveland who was born on July 21, 1864. Excerpted from Ladies, First: Common Threads.

Comments